WV Science News

Updates from Senior Scientist Than Hitt for WV Rivers Coalition

Fall 2025

What’s Inside

- Science Feature: Impaired streams predict cancer rates in West Virginia

- WV Stream Watch App in Action: Fifteenmile Fork in Kanawha County

- Water Quality Standards: What you need to know about Selenium

- Monitoring Update: New team forms in Jefferson County

- Survey Results: Science needs and priorities for WV watershed organizations

- Technical Review: DEP’s 2024 Clean Water Act reporting

- What We’re Reading: New research on Appalachian waters

Science Feature: Impaired streams predict cancer rates in West Virginia

by Daisy Fynewever, Georgetown University

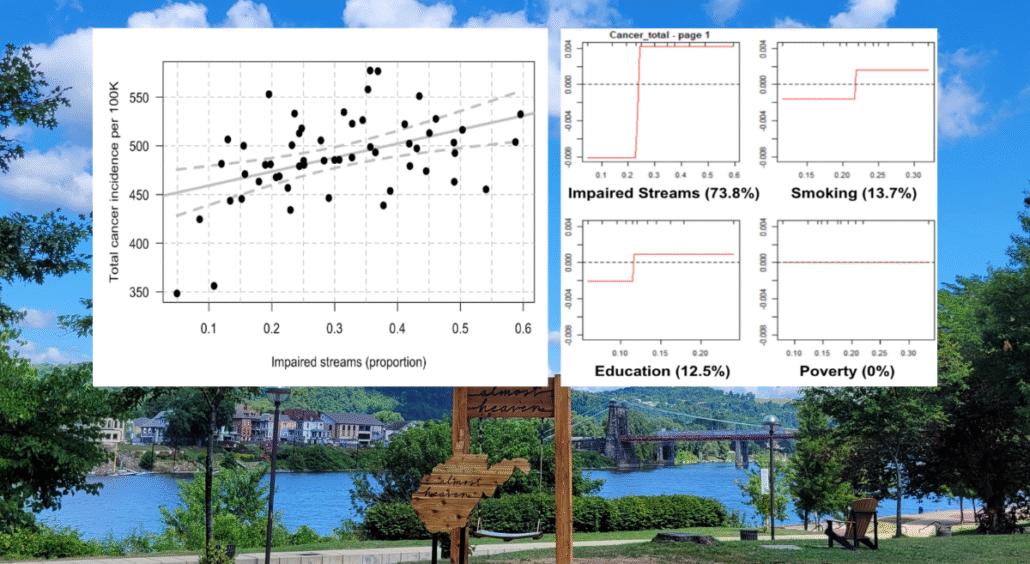

County-level relationship between cancer rates and impaired streams in WV (left panel) and boosted regression partial dependence plots showing the association of predictors to cancer rates while controlling for other covariates (right panel). The percentage values indicate the relative importance of each variable in the model.

This summer I collaborated with Senior Scientist Than Hitt on a research project to explore connections between water quality and public health in WV with support from Georgetown University’s Social Responsibility Network.

I was interested in learning more about how environmental degradation affects communities, and, although the socioeconomic and environmental challenges in Appalachia are well known, we still have much to learn about the link to environmental health and public health. I was specifically curious about whether water quality in streams and rivers could be used to predict public health outcomes and whether environmental predictors were more or less informative than socioeconomic predictors for public health, such as smoking or poverty rates.

To investigate this, we compiled socioeconomic and public health data from the Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, and the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, and we selected variables for analysis including county-level cancer incidence, smoking rates, poverty rates, and education rates. We then compiled data about the quality of streams and rivers in WV. We mapped the distribution of impaired waters across the state from the DEP’s 2016 Integrated Report (the most recent year that GIS data was available for analysis). These streams are known as the “303d” impaired streams in reference to the section of the Clean Water Act. We calculated the proportion of impaired streams for each county based on the National Hydrography Dataset map of all streams. With our dataset assembled, we used linear regression and machine learning methods to evaluate the relationships between stream impairments and public health.

Here’s what we found: both statistical approaches revealed higher cancer rates in areas with more impaired streams. Impaired stream proportion also had more predictive value for public health than smoking rates or other covariates (Figure 1). Our analysis showed that the state of our streams is important information for public health as well as for wildlife and ecosystem conservation. Prior research has shown that stream benthic macroinvertebrate communities can predict public health outcomes in WV (Hitt & Hendryx 2010; EcoHealth 7:91-104), and our results expand this finding and suggest that other causes of impairment (such as bacteria or toxic metals) also have predictive power.

Our study also opens the door to more questions. Although impaired streams were statistically related to cancer rates, we did not investigate if it was a causal effect or if other factors were more important. Additionally, the cancer data we utilized was collected via phone survey, which may bias the data itself. One thing is certain, however: an accurate assessment of impaired streams in WV is more important than ever.

Our analysis is still ongoing, and I am excited to continue to investigate links between water quality and public health in West Virginia and beyond.

WV Stream Watch App in Action: Fifteenmile Fork in Kanawha County

The confluence of Fifteenmile Fork (right) and Cabin Creek (left) at coordinates 38.017848, -81.420474 in Kanawha County, WV.

It’s said that a picture tells a thousand words – and that is especially true for photos with the WV Stream Watch App.

For example, consider this photo of the confluence of Fifteenmile Fork and Cabin Creek in Kanawha County: Iron precipitates are clearly seen in water from Fifteenmile Fork, but not Cabin Creek. This cannot be a regional effect, but rather must be localized to the Fifteenmile Fork watershed.

We reviewed mining information about this site in DEP’s TAGIS webmap. We found that coal NPDES permits are present upstream from this confluence in both streams. However, only the Fifteenmile Fork is reported to have underground mining in the TAGIS webmap. The extent of surface mining permit boundaries also appear to be more extensive in Fifteenmile Fork than in the Cabin Creek watershed upstream from this confluence.

Based on this photo documentation, we filed a complaint with DEP and requested they investigate the site, update associated NPDES permits if needed, and conduct remediation actions. We also explained that this may be a violation of state code prohibiting pollution that causes a “distinctly visible color” in state waters (§47CSR-2-3.2.f) as well as state code prohibiting “distinctly visible floating or settleable solids” in state waters (§47CSR-2-3.2.a).

In response, DEP officials confirmed that they will conduct an investigation, and we will keep you informed.

Water Quality Standards: What you need to know about selenium

An example of selenium contamination in creek chub observed by US Geological Survey researchers in the Mud River downstream from the Hobet 21 mine complex.

A proposal to weaken the water quality standard for selenium (Se) may be considered by the WV legislature in 2026. So let’s take a step back and briefly review the science and why it matters.

The first thing to know is that Se is an essential micronutrient for animals – meaning that all animals need it for normal functioning but cannot produce it so must consume it in their diet. But once those dietary needs are met, Se rapidly becomes toxic. In fish, excess Se can cause misshapen backbones, warped jaws, or more extreme malformities in early life stages. Waterfowl also can suffer embryonic deformities as well as organ damage that reduce their survival. That’s because waterfowl often rely on wetland habitats that are connected to streams where Se loads can be highest.

The second thing to know is that Se naturally occurs in some rock formations across Appalachia – particularly near coal deposits of the Allegheny and upper Kanawha formations. When the coal is mined, rain dissolves Se from the rocks and flushes it into streams and rivers where it becomes incorporated into foodwebs impacting fish and wildlife. As a result, Se contamination often is one of many downstream effects of coal mining in Appalachia.

Another important consideration is that compliance with the Se standard can be assessed from fish tissue or aqueous Se in the water column. The current water quality standards in WV give primacy to fish tissue results (in part because biological tissue is more relevant for toxicity than aqueous concentrations) but aqueous samples still are meaningful and useful. The proposal to weaken the standard would increase the amount of allowable Se in fish tissue from 8.0 to 9.5 ug/g (micrograms per gram) citing EPA methods.

However, EPA also recommends a more protective aqueous standard than WV currently has (3 vs 5 ug/L, micrograms per liter): Therefore if the fish tissue standard is to be weakened based on EPA guidance, the aqueous standard should be strengthened for the same reason.

West Virginians are paying attention! Nearly 500 comments were submitted to DEP from the WV Rivers action alert earlier this year, and the social media posts reached over 20000 views.

This week in Charleston during the December Interims, members of the Legislative Rule Making Committee adopted this change and WV Rivers Coalition is deeply disappointed by this decision despite public advocacy on the issue.

We expect that this will continue to be one to watch in the upcoming legislative session. Please contact Than Hitt nhitt@wvrivers.org for more information and to get involved.

Monitoring Update: New team forms in Jefferson County

Tamar Kavaldjian-Liskey at the Turkey Run sampling site in Jefferson County.

Lake Louisa in Jefferson County is one of the largest limestone springs in the state, and Turkey Run flows from the lake into Opequon Creek and then the Potomac River. This place is not only of immense ecological and cultural importance – it is threatened by a proposed water bottling plant that would extract significant quantities of groundwater that could affect the spring and downstream waters. In response, a team of volunteers with Protect Middleway has stepped up to collect baseline monitoring data in Turkey Run. They’re doing great with 17 surveys conducted in just a few months! Tamar Kavaldjian-Liskey and team are collecting data on turbidity, pH, conductivity and water temperature.

Survey Results: Science needs and priorities for WV watershed organizations

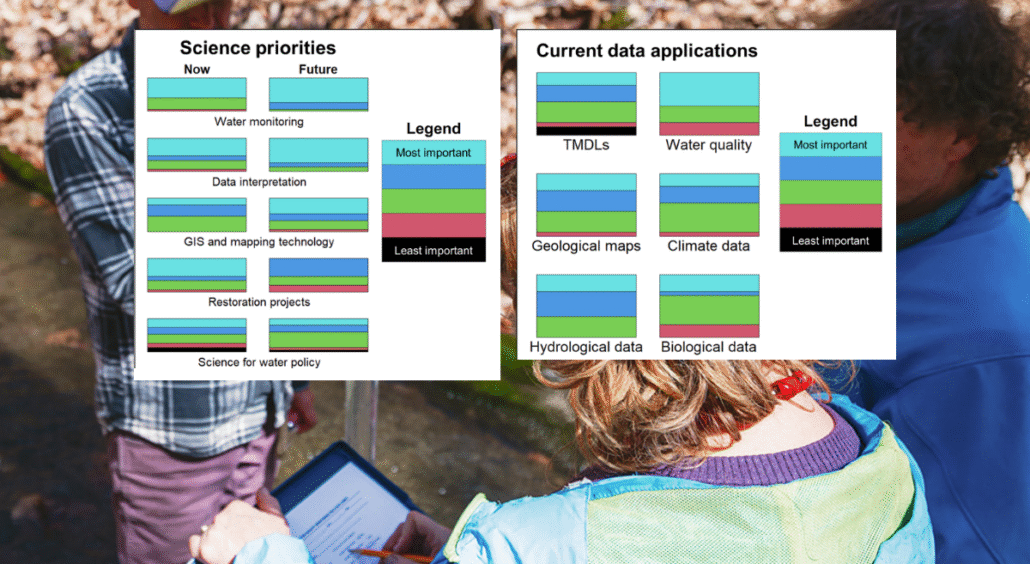

Figure 1. Survey results for current and future science priorities. The size of each colored section indicates the proportion of responses in that category. Figure 2. Survey results for current data applications. The size of each colored section indicates the proportion of responses in that category.

Science often plays a pivotal role in the work of watershed organizations. From restoration projects to water monitoring to education and outreach, science can be essential to the foundational mission of watershed groups. However, organizations often have different priorities and needs for technical support. We therefore conducted a survey of watershed organizations to address these issues at the 2025 WV Watershed Symposium.

We received responses from 15 organizations representing regions across the state. Responses also represented newer and older organizations, as well as organizations with full-time staff and those relying solely on volunteers. The survey included questions on current and anticipated future science priorities as well as current data applications. Although this survey is by no means a census of all perspectives, we hope the results represent a meaningful sample of science needs to inform new strategies for technical support moving forward.

First let’s look at science priorities and how these are anticipated to change over time (Figure 1). Respondents indicated that all science categories were somewhat important for their current and future work (i.e., green, dark blue, and light blue sections in Figure 1). However, water monitoring, data interpretation, and restoration projects ranked above GIS applications and technical reviews for water policy. Respondents also anticipated increasing needs for scientific support for water monitoring, data interpretation, and GIS mapping technology in the future. In contrast, technical support for restoration projects policy became less of a priority for anticipated future needs (Figure 1).

Now let’s look at how important different kinds of scientific data are for organizations currently (Figure 2). Here we see substantial diversity in responses. For example, analysis of TMDLs (total maximum daily loads) was “most important” for some organizations and “least important” for others. Likewise, applications of water quality data, geological maps, climate data, and biological data showed a similar pattern. In contrast, all respondents indicated that applications of hydrological data (e.g., stream flow) were moderately to highly important for their current work.

The survey also revealed several important partnerships for science support currently underway. For instance, respondents reported collaborations with local universities and high schools, WVDEP staff, WVU Water Resources Institute, WVU Mountain Hydrology Laboratory, as well as nonprofit organizations such as the Downstream Project and WV Rivers Coalition. Respondents also indicated their interest in technical trainings for Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP) development as well as acid mine drainage treatment, stream geomorphology, groundwater chemistry, and karst hydrogeology.

Respondents also identified specific projects with specific scientific and technical needs. These include environmental DNA (eDNA) and bacterial assessment as well as technical support for watershed conservation plans. One respondent suggested development of a science advisor platform online that could be used to provide technical assistance for various projects. These survey results give us a lot to consider as we develop new strategies to provide technical assistance for WV watershed organizations moving forward.

Technical Review: DEP’s 2024 Clean Water Act reporting

DEP’s draft 2024 Integrated Report can be accessed here.

Every 2 years, the Clean Water Act requires states to update their assessment of streams and rivers, including an analysis of which waterbodies are meeting water quality standards and which are not (CWA section 303d) as well as an analysis of the overall condition of water resources statewide (CWA section 305b). This is often referred to as the “Integrated Report” (IR) because it includes both assessments, and it’s important because it can direct where cleanup and restoration plans will be developed.

In July, DEP released a draft of their 2024 Integrated Report for public review. We compared the new report against prior assessments to evaluate what has changed and whether the methods were scientifically defensible. Here’s what we found: the draft report includes an improved method for biotic assessments with genus-level benthic macroinvertebrate data, but unfortunately the benefits of this approach are undercut by inaccurate characterization of reference conditions which ultimately weaken water quality protections and preclude necessary restoration efforts.

Specifically, the draft IR departs incorporated a novel “Level-4 reference condition tier” into the analysis of impaired streams. The stated intent of this new reference category is to “set expectations for attainment that allow for land use development and particularly point and non-point sources [of pollution]” (IR page B-3) but that is not an appropriate purpose of reference conditions for Clean Water Act assessments. As a result of this change, DEP has significantly lowered the expectations for what it takes to support Aquatic Life Use as required by the Clean Water Act. We therefore are encouraging DEP to improve the draft IR by revising or removing the flawed Level-4 reference category.

Our technical review is making a difference. We were cited in reporting by the Charleston Gazette, and hundreds of West Virginians sent comments to DEP from the WV Rivers Action Alert. We expect revisions to the IR to come out soon, so stay tuned for updates!