Monitoring Newsletter: Winter 2025 Edition

This image of Dry Run on February 3 was collected as part of the Water Quality Monitoring Project. They observed partly cloudy skies and no recent rain, but Dry Run was running high with off-color water. pH measured at 4.5, with a conductivity of 55 uS/cm and turbidity at 4 NTU. Air temp was 46°F, and the water a chilly 44°F.

What’s inside:

- Introducing the Wheeling Creek Watershed Alliance

- All-Star Volunteer Spotlight

- WV Stream Watch App in Action

- Applied Science: Corridor H Baseline Monitoring

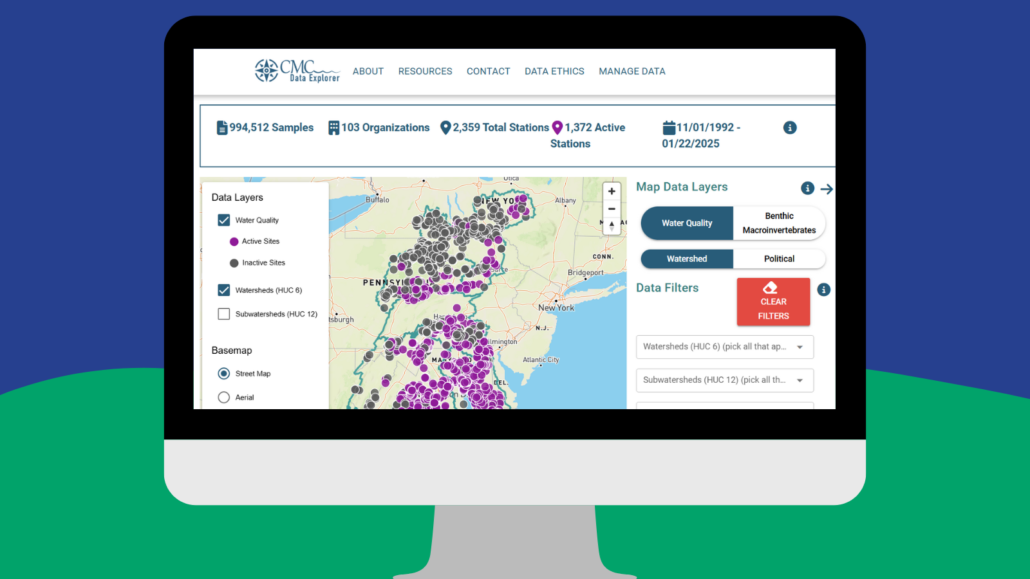

- Data Tools: A New Platform for Stream Data Visualization in the Eastern Panhandle

Introducing the Wheeling Creek Watershed Alliance

A conversation with Dr. James Wood, West Liberty University

James Wood in his native habitat, paddling! In the background, Ethan Brant collects a water quality sample in a tributary to Wheeling Creek. Photos Courtesy of James Wood.

When was this organization formed, and what was your motivation?

We have been meeting for about 2 years, and our motivation is multifold: we aim to increase recreation on Wheeling Creek for the enjoyment of the community and to support the local economy. We also hope to create more connections between the community and the creek — and, by extension, improve water quality — so the creek is a cleaner and safer play for kids to play and for families to enjoy.

What have you accomplished so far?

We have created a network of engaged local citizens interested in improving water quality in Wheeling Creek. We have been awarded multiple grants to improve educational outreach about the creek. These have included funding to install kiosks along the creek so people know where to put kayaks in and take them out, and create a river map showing recreational “blue trails.” We are also working to improve relationships with the City of Wheeling for us all to appreciate the value the creek brings to the city and community.

Wheeling Creek is a fantastic natural resource for the community. It has almost 30 boatable miles when the creek is up and is a gentle float with only a few minor (Class I) riffles to navigate. And, the creek is popular with anglers for its smallmouth bass fishery and stocked trout fishery during spring months. It also has a greenway running alongside it for several miles near the city of Wheeling, so it is accessible, too!

What do you hope to do moving forward?

We are hoping to become an official 501c3 organization in the coming year and to organize more river cleanups and community kayaking events. Our goal is to not only beautify the creek, but also to continue to build relationships between the community and the creek so that both can prosper.

For more information and to get involved: https://www.facebook.com/WheelingCreekWatershedAlliance

All-star volunteer spotlight: Kate Lehman

Kate Lehman, with a photo from Warm Springs Watershed Association in the background. Warm Springs Run is an 11.8-mile stream in Morgan County, WV, that empties directly into the Potomac River according to their website.

Kate Lehman’s work with the Warm Springs Watershed Association in Morgan County sets a gold standard for community stream monitoring. She has personally conducted more than 80 stream surveys over recent years, including diligent calibration of equipment and extensive data compilations. Here she shares some thoughts on why she’s doing this work and advice she can share.

When did you first start volunteering as a stream monitor?

The Warm Springs Watershed Association was formed in 2008. We started our monitoring program in 2009 with equipment, help and guidance from Tim Craddock of the WV Save Our Streams program and members of the Sleepy Creek Watershed Association, who had an established history of stream monitoring.

In 2021, construction began on a four-lane bypass project in the upper watershed. One hundred and seventy-five acres of trees and ground cover were destroyed during construction. Concerned about erosion, we formed an alliance with WV Rivers and Trout Unlimited to do further monitoring. Grant funds provided digital equipment and Jenna Dodson from WV Rivers conducted training. We continue to do weekly monitoring at several potentially affected sights on Warm Springs Run. We also monitor after a rainfall of more than ¾ of an inch.

What was your motivation when you started? How has this changed over time?

Watershed protection and preservation was a new topic to me when WSWA was established. It didn’t take long to realize how regular stream monitoring could provide information on what was happening in an already impaired stream. My motivation was enhanced by a visit to the USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center at the Leetown Research Laboratory, where we learned that scientists at that organization had been using the information we provided. It made a difference to me to know that our work was important not just at the local but at the national level.

What challenges have you faced doing this work?

I was a Unitarian Universalist minister before I retired and moved to Morgan County, WV in 2006. In that job part of my success was based upon the fact that I’m a “big idea” rather than a detail person. Thus, there was a steep learning curve when I first began monitoring Warm Springs Run. In addition to learning how to identify macroinvertebrates, we had to learn the proper protocol for monitoring. For example, I did not know it makes a difference in how one adds a solution to a bottle to determine, for example, the alkalinity of the sample.

When we were provided with digital equipment to do monitoring for the WV Rivers/Trout Unlimited program, it became necessary to learn how to calibrate the equipment, something we do every time we monitor. I did not learn this skill quickly or easily, and I still review the process when we resume monitoring when weather is warmer. However, I find data entry to be torture. The TU info can be entered from a phone while in the field, which makes a huge difference to me.

What advice would you give other organizations getting started in stream monitoring?

Start small. In the beginning we identified macros at level 1 and eventually progressed to providing more information. Take advantage of every learning opportunity; attend workshops more than once to reinforce what you’ve learned. Establish a team; spending time with friends is part of the reason I like monitoring. Learn how you benefit personally from monitoring; for example, I’ve discovered that when I’m having a bad day, I am calmed and revived by spending time in the water. This information provides a personal incentive to participate.

Applied Science: Corridor H Baseline Monitoring

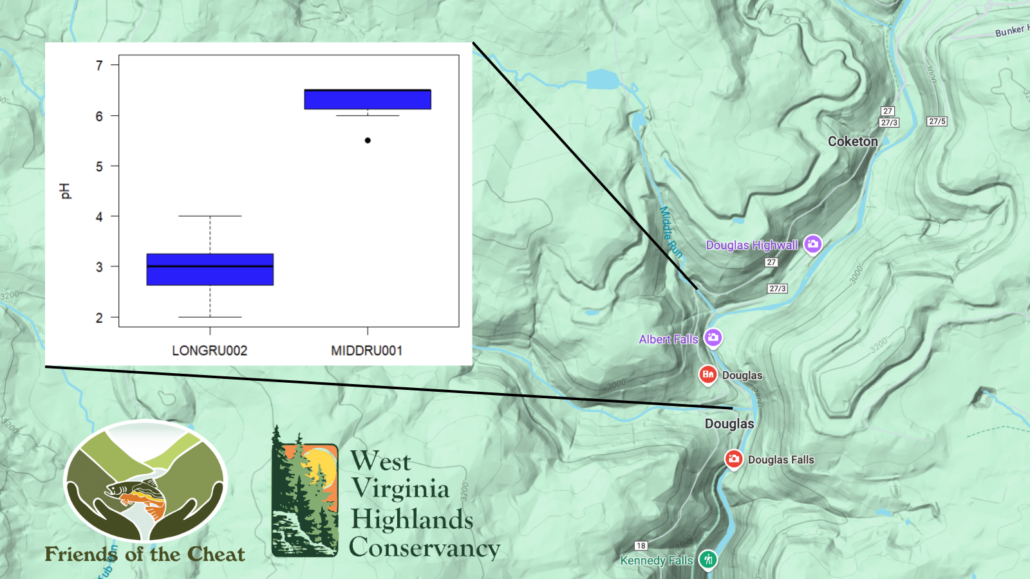

Observed pH in Long Run (LONGRU002) and Middle Run (MIDDR001) in the North Fork Blackwater River basin from 2022-2024

Volunteers with Friends of the Cheat and the WV Highlands Conservancy have been hard at work documenting baseline conditions in advance of Corridor H development from Parsons to Davis.

The team of volunteers includes: Bret Rosenblum, Kay Hart, Mimi Kibler, Jane Birdsong, Blaise Hollot, Chris Byrd, and Randy Kesling, with technical and logistical support from Madison Ball (Friends of the Cheat) and Susan Rosenblum (WV Highlands Conservancy).

The team has conducted more than 180 stream surveys since 2022 using the platform launched by Trout Unlimited and WV Rivers on CitSci.org to document attributes of water chemistry and physical habitat. A map of the sample sites and preliminary data plots can be found here. Importantly, their surveys include samples from all seasons (yes, winter, too!) and include samples collected after heavy rain, light rain, and no rain. This sampling effort is essential for understanding seasonal variation and land use’s effects on turbidity and other parameters. Kudos!

A primary concern focuses on the potential for road construction to increase acidity (decrease pH) due to soil disturbance or mobilization of acid mine drainage. Their monitoring data clearly indicate that streams in the region can show vastly distinct pH signatures, and extremely acidic conditions are already present in some streams in the region.

Consider this example: Long Run (site LONGRU002) is much more acidic than Middle Run (site MIDDR001), even though both sites are very close to each other (< 0.5 km) where they flow into in the North Fork Blackwater River watershed. Moreover, the median observed pH in Long Run is 3 units, roughly the acidity of grapefruit juice (!). Clearly, acidic conditions are present in the potential path of Corridor H west of Thomas, and this could have dire implications for downstream water quality as well as brook trout and other aquatic organisms. And here’s another important point: DEP data collected from Long Run at a separate location are consistent with these observations (see DEP database here), so this builds confidence in the reliability of community monitoring data — and this is particularly essential where citizen monitoring is conducted but DEP data are not available.

For more information on the status of Corridor H, see WV Highlands Conservancy updates here.