West Virginians for Public Lands

Summer 2024

We Were Not the First: Indigenous Impacts in Appalachia

West Virginia was not empty and barren when settlers first crossed the Appalachian Mountains to enter into the place we call Almost Heaven.

The seasonal exhibit “Creating Home: Indigenous Roots and Connections in the Appalachian Forest” explores the Indigenous influences in West Virginia and the Appalachian Forests. It is on display now at the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area (AFNHA) Discovery Center in Elkins.

The 2024 seasonal exhibit starts with the idea of homemaking in Appalachia. Indigenous people were the first to live on and love this land, and their connections to it and influence on Appalachian culture continue today.

One of the themes of this exhibit is (Re)Calling the Names. (Re)Calling the Names means both remembering the names that Indigenous communities first gave to these places and actively reading and saying these names again.

Visitors to the AFNHA Discovery Center can learn about indigenous influences in the Appalachian Forest

Beyond sharing stories of Indigenous language revitalization and the long history of multicultural communities in this region, the exhibit includes a map originally designed for the WVU Libraries’ exhibit “Indigenous Appalachia.”

Many of the names on this map are rivers, which demonstrates the deep importance of these waterways to communities past and present. The names of Indigenous Nations and communities are all over this state and region as a whole. Place names like Seneca Rocks and Mingo County remind us all that Native communities first made their homes here. The map shows the names that those Indigenous communities applied to the landscape themselves, offering a new learning opportunity to all who enjoy the beauty of West Virginia.

A couple of other highlights from the exhibit:

- Sustainability practices in use today are only just catching up to the traditional ecological knowledge that Native communities have held for so many generations. Controlled burns and other forest management practices that government agencies and conservation organizations employ today have often long been a part of Indigenous land stewardship and relationships.

- Fun fact: Bison were in West Virginia! Melissa Thomas-Van Gundy of the Forest Service has done recent research on this and connected it to current plant ranges.

The blog “Remembering West Virginia’s Indigenous History” by Dr. Joe Stahlman, a primary consultant for the exhibit, provides more information about the impacts on Indigenous peoples in Appalachia.

The exhibit is on display through the end of October in the Appalachian Forest Discovery Center in Darden Mill, 101 Railroad Avenue, Elkins. Information about the exhibit is also available virtually.

West Virginians for Public Lands thanks Eleanor Renshaw, Americorps with AFNHA, Appalachian Forest Discovery Center, for this article and the information presented. Eleanor is responsible for putting together the exhibit. Larry Jent of AFNHA staff also provides much knowledge regarding Indigenous peoples of Appalachia.

Comments Due 9/20 on Forest Service Plans to Manage Older and Old Growth Trees and Forests: Look for YOUR Opportunity to Comment

Old Growth rules should ensure that areas like Gaudinier Scenic Area, which has old-growth trees from the Mon Forest, are protected.

As we talked about last month, the USFS recently released its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the “Land Management Plan Direction for Old-Growth Forest Conditions,” which considers the impact of amending all 128 forest plans in one action to consider old and older growth trees and forests.

The Draft EIS and related documents are here.

The Forest Service’s decision to protect old growth is vitally important to West Virginians.

Eastern U.S. forests were clear-cut in the first two decades of the 20th century. The most ‘mature’ forests in these areas are about 80-100 years old.

Policies or definitions of “old growth” must consider the unique circumstances in the Mountain State.

We want you to be involved! We will be providing a link in our next issue of Public Lands News for you to make your opinions known directly to the Forest Service.

Mon Forest Headwaters: What do West Virginians Think?

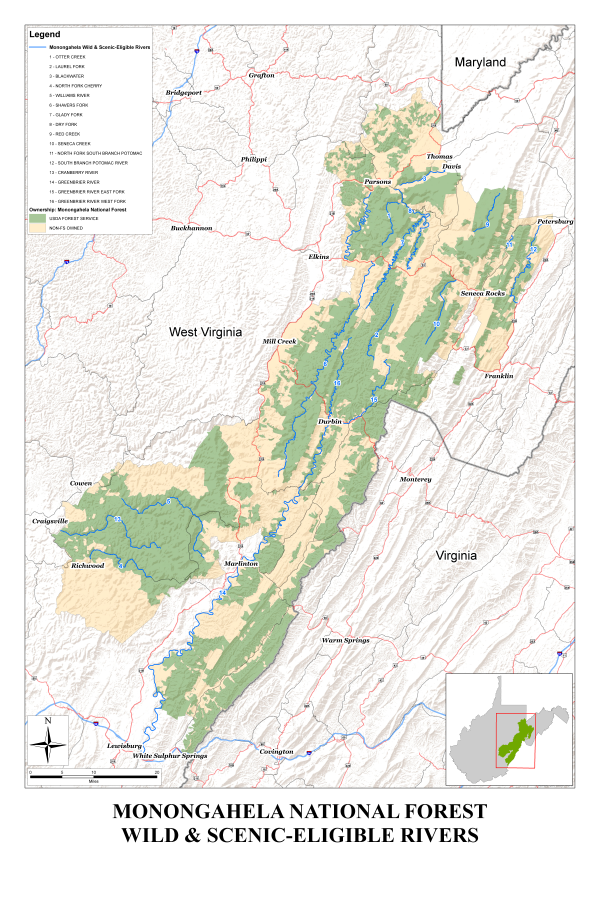

Last month, we discussed the U.S. Forest Service’s identification of 16 waterways within the Monongahela National Forest as eligible for Wild and Scenic designation. The Forest Service has been protecting these streams for their remarkably outstanding value. You can learn more about outstandingly remarkable values in this summary from the National Park Service.

The map shows the 16 waterways: the Blackwater, the East Fork of the Greenbrier, the West Fork of the Greenbrier, the Greenbrier mainstem, Shavers Fork, Dry Fork, Glady Fork, Laurel Fork, Otter Creek, Red Creek, Seneca Creek, North Fork of the Cherry, Cranberry, Williams, South Branch of the Potomac, and the North Fork of South Branch of the Potomac.

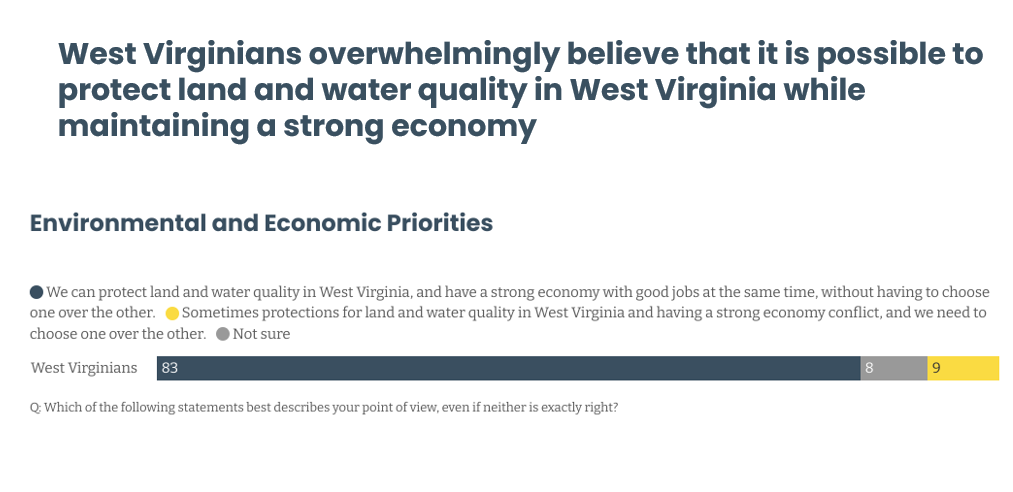

But how do West Virginians prioritize economic development over protecting our public lands and waters? And what do Mountain State residents think about permanent safeguards for these waters?

Recent polling answers these questions. West Virginians believe you can have both ecosystem safeguards and economic opportunities. Regardless of political preferences, 85% of us believe that we should have permanent safeguards on these irreplaceable Mon Forest headwaters.

Visits to protected waterways generate direct spending and indirect community economic benefits such as increased employment in businesses not directly involved in outdoor recreation opportunities including restaurants and other hospitality businesses. Once again, public lands and waters are good for business.

Simply put, permanent safeguards ensure our legacy of clean drinking water, healthy aquatic ecosystems, and our heritage of nature-based recreation. Here’s some more information about the importance of Mon Forest Headwaters. We also want YOUR opinion: tell us your concerns and ideas about permanent protections for Mon Forest Headwaters. After all, the Candy Darters and Hellbenders are depending on us!

Local Public Lands: Airport Confirms Not Proceeding with Runway Plan

Friends of Coonskin Park advocate for the protection of local public lands.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and Charleston’s Yeager Airport previously announced a “pause” on runway expansion. The halt of this bad idea was confirmed at public meetings on July 9, 2024. The airport instead will focus on terminal renovations. If you could not make it, here are the displays from the Public Meeting.

Proposed runway expansion plans would have involved moving 25.6 million cubic yards of dirt and filling in the forested areas of Coonskin Park, a beloved county public land. Charleston’s drinking water intake and the lower Elk River would have been at risk.

Theoretically, the airport could one day come back with this plan or a new plan. But until then, our public land has been protected!

Get Real World Experience in Public Lands Advocacy

Love public lands? Want to get some experience in advocating for public lands?

West Virginia Rivers Coalition is looking for a contractor to build individual and business support to provide permanent safeguards to Mon Forest headwaters. The contracted position is for 10-20 hours per week, at $25 per hour. For more information email Mike Jones, or send a resume to mjones@wvrivers.org.

National Park Conservation Association is looking for a West Virginia Outreach and Engagement Intern to support outreach and engagement efforts focused on protecting national parks. This is a part-time, remote/hybrid opportunity (up to 20 hours per week at $20 per hour) with a flexible schedule.

For more information: https://npca.hire.trakstar.com/jobs/fk0v5lq?pjb_hash=Y7bAmjMPq4

If you want to show your love for public lands, take advantage of these opportunities!